It’s almost impossible these days to open a media magazine or web page and not see some mention of IMF. From end users to equipment manufacturers, everybody seems to be talking about IMF and how important it is for the industry to embrace it. But what is IMF? Why should you care about it? This paper will examine the business reasons for the rise of IMF – with the minimum amount of technical jargon. Technology itself is seldom interesting unless it solves a particular business issue – so that will be the focus of this introductory paper.

The Problem?

IMF (the Interoperable Mastering Format) was formulated by the Hollywood community in conjunction with SMPTE (the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers), and is designed to remove the issue of creating and managing multiple versions of the same title – an increasingly problematic issue for companies involved in the creation and distribution of content. Producers of programming, both long and short form, want to garner the maximum revenue from each title they produce. To do that, they need to deliver those titles to as many distribution points as possible. A major motion picture will be produced in multiple languages, with multiple sets of titles, local language subtitles, etc. Different deliverables may require that the program itself be re-edited to remove material that would be considered offensive in certain cultures, or to remove tail logos (or any material relating to an aircraft accident) from airline cuts. To date, this has meant that the same title will have to be re-edited over and over and over again – and that need continues to grow as the number of outlets/playback systems continues to grow. One major motion picture studio has gone on record as saying that it is not unusual for them to create 3,500 versions of the same title in order to satisfy the requirements for all of their world-wide deliverables. Think about that for a moment: 3,500 versions of the same movie – now multiply that by the number of movies produced per year, and you can quickly understand why this is a huge cost-sink for these businesses.

The same is true, of course, for companies producing material for TV consumption. They have all of the same issues as the film companies, plus closed captioning and other government-mandated content adjustments. Plus, they now need to consider delivery to newer, portable playback devices…

This proliferation in deliverables is exactly what IMF is designed to address.

So now you can have a single package containing all the media items, plus the adjustments that need to be made in order to create all of the final variants of the title. Clearly, in the example of the motion picture company mentioned above, they themselves (in theory) only have to create this package once, and the final delivery points, located in various geographies around the world, can then conform the culture-appropriate version for distribution. The added complexity is that the package must also contain all of the change information that’s required for each version – rather like distributed EDLs. But these “change orders” – called “Composition Play Lists”, or CPLs – and the associated replacement video/audio/captions/subtitles take up much, much less storage and bandwidth than repeating custom video tracks for each deliverable.

This is not a new concept: more than 10 years ago, AMWA (the Advanced Media Workflow Association) – a community-driven forum for networked media workflows, released an MXF-based application specification called “AS-02”, which set out to solve the same problem in broadly the same way – though really only targeted at the Broadcast market. It garnered some success, but was never an industry standard, as AMWA is not a standards body. IMF, as a ratified SMPTE project, is an industry standard encompassing both television and motion picture requirements, and is therefore gaining much wider acceptance world-wide.

Why should you care?

IMF is gaining increasing traction, as it dramatically simplifies and reduces the expense of both delivering and receiving titles for ultimate distribution to multiple destinations. It has clear benefits for those companies producing motion picture titles, and also simplifies and reduces costs in receiving those titles and preparing the final deliverables to those audiences. In fact, Netflix has had delivery in IMF as a requirement for certain formats for a few years. The recent initiative by NABA (the North American Broadcasters Association) to standardize the delivery formats used between and within broadcast companies is basing its work on the successful solution used for the same purpose in the UK and is focusing its initial work on specifying IMF as the “business-to-business” format of choice between its members – a smart choice, considering that the number of manufacturers offering products that support the creation of, and consumption of, IMF packages continues to proliferate. Other national broadcasters are poised to follow suit.

At Telestream, we are committed to supporting the IMF format. Vantage is already IMF capable, and the features that support this new format continue to extend the product’s reach. No matter what your IMF processing requirements are, we have a product to help you further increase your profitability.

The solution:

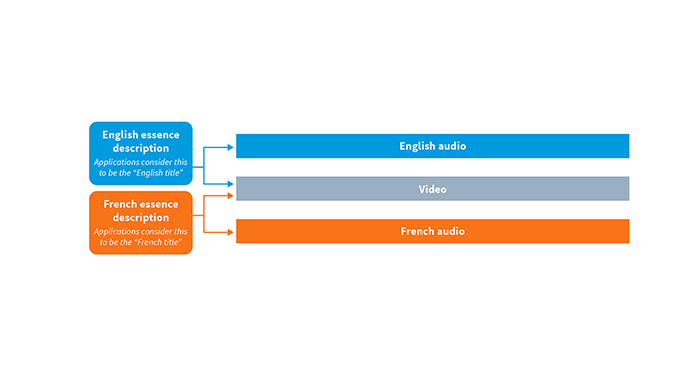

To understand the solution, we must first examine the typical differences between these individual versions. Firstly, there is the need to create language-specific versions of a program. If we consider the individual assets involved in any rendition, it is easy to see that the major difference, of course, is in the dialog. Let’s consider an example movie – “Gone with the Wind”. It has been released in all the major European languages, along with several Arabic and Asian tongues (though some phrases had to be edited out to avoid offense in certain geographies). If you look at the body of the piece, the only real difference is in that dialog track. But the producers had to create individual complete versions of the programming for each language. That means that video, which was the same in every case, was also duplicated for each deliverable. It would be much more efficient to deliver the movie as a package containing a single video track with multiple dialog tracks, and have the final delivery point select the required audio track (see figure 1).

The same applies for any written content in the movie – such as posters or newspapers shown in cutaways – instead of delivering a completely new video track, deliver the main version along with replacements for just those cutaways, and have the final delivery point effectively “edit in” the language appropriate version. Start and end credits can also be changed in this way, accommodating new voice talent credits etc. (see figure 2). Scenes considered inappropriate in certain deliverables (plane crashes in airline cuts, for example) can simply be marked for removal in that version, again at the point of final delivery.

To learn more watch our webinar, The Business Case for IMF.